To continue the March series of articles on women, we are pleased to introduce a woman who greatly contributed to the understanding of cell fate in the development of amphibian embryos, such as Xenopus laevis. This woman is Hilde Mangold, a German biologist of the early 20th century.

Biography

Hilde Mangold, previously Proeschold, was born on 20 October 1898 in Gotha in Germany (1–3). At the age of 16, she entered the Gymnasium Ernestinum where she was one of the only girls. She was then placed in a school to learn domestic chores and how to respect social codes. However, only after 6 months, she decided to enroll her university studies in chemistry at the University of Jena (1,3). At the end of 1919, she moved to Frankfurt where she mainly studied zoology (3).

In Frankfurt, Hilde heard a guest lecture by Hans Spemann, a well-known german embryologist, and it was at this point that she decided to move to Freiburg, where Spemann had just been called to the chair of zoology. After one year, she was accepted for a PhD position under Spemann’s supervision (3) and after a failed PhD topic, Hilde changed the topic of her thesis to do experiments with transplants on newt embryos. This work introduced the term “organizer” (4) which was a revolution in the understanding of embryology (1).

In 1921, Hilde Proeschold became Mangold by marrying Otto Mangold (1,3) and together they had a son, Christian, born in December 1923 (3).

However, and unluckily, Hilde’s life was rather short, as in September 1924, when she was 25, she died after being severely burned while she was filling the cooker with alcohol.

Hilde Mangold’s contribution to the concept of organizer

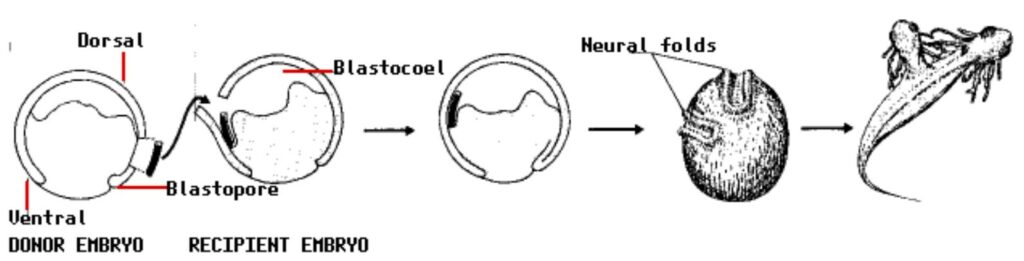

For her thesis work, Hilde worked with amphibian embryos. Hilde transplanted the dorsal blastopore lip, a structure that forms during early embryonic development, into the belly region of a host embryo from another species (3). The goal of the experiment was to induce the development of a second body axis on the host organism (6). Hilde first did her manipulations with newt embryos and after she confirmed her hypothesis with Xenopus laevis (3,4,6).

In 1920, antibiotics did not yet exist and most of the embryos showed deadly bacterial infections, which made it difficult to get conclusive results on the experiments (4). But after two years of experiments and perseverance, Hilde Mangold successfully achieved the experiment.

Some days after the transplantation, she observed the entire neural tube and brain formation. The final result was two embryos joined at the gut (7), which was the proof that the transplanted cells were inducing host cells to migrate and adopt specific cell fates (6).

Hilde’s dissertation on this topic was the foundation of her mentor’s Nobel prize. In 1935, 9 years after Hilde’s death, Hans Spemann received the Nobel prize in physiology or medicine for the discovery of the embryonic organizer (8). In this sense, Hilde’s work was “one of the very few doctoral theses in biology that have directly resulted in the awarding of a Nobel Prize” (9).

Conclusion

At only 25 years old, Hilde Mangold’s experiments led to a major step forward in embryology and the introduction of the term embryonic organizer.

To not forget her important contribution and in memory of Hilde, one of the buildings of the University of Freiburg is named after her.

References

- Hilde Mangold (1898-1924) | The Embryo Project Encyclopedia [Internet]. [cited 2023 Mar 20]. Available from: https://embryo.asu.edu/pages/hilde-mangold-1898-1924

- Women In Science – Hilde Mangold [Internet]. [cited 2023 Mar 20]. Available from: https://sites.google.com/laudefontenebro.com/womeninscience/twentieth-century/hilde-mangold

- Fiissler PE, Sander K. Hilde Mangold (1898-1924) and Spemann’s organizer: achievement and tragedy.

- Hamburger V. Hilde Mangold, co-discoverer of the organizer. J Hist Biol. 1984;17(1):1–11.

- Hilde Mangold. In: Wikipedia [Internet]. 2023 [cited 2023 Mar 22]. Available from: https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Hilde_Mangold&oldid=1136188172

- Women in Science: Hilde Mangold and the embryonic organizer [Internet]. The Jackson Laboratory. [cited 2023 Mar 23]. Available from: https://www.jax.org/news-and-insights/jax-blog/2016/October/women-in-science-hilde-mangold

- Spemann-Mangold Organizer | The Embryo Project Encyclopedia [Internet]. [cited 2023 Mar 23]. Available from: https://embryo.asu.edu/pages/spemann-mangold-organizer

- The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 1935 [Internet]. NobelPrize.org. [cited 2023 Mar 23]. Available from: https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/medicine/1935/spemann/biographical/

- Hilde Mangold. In: Wikipedia [Internet]. 2023 [cited 2023 Mar 23]. Available from: https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Hilde_Mangold&oldid=1136188172

Organizing the Embryo: The Central Nervous System [Internet]. [cited 2023 Mar 23]. Available from: https://www.biology-pages.info/S/Spemann.html

First image : Hilde MANGOLD [Internet]. [cited 2023 Mar 22]. Available from: https://scientificwomen.net/women/mangold-hilde-149