Handling zebrafish embryos may seem simple, but doing it at scale is often a real challenge. This month’s article explores how workflows are shifting toward automation to support higher throughput, better reproducibility, and streamlined research processes.

Introduction

Zebrafish embryos have become an essential model for studying development, toxicology, and disease, offering a unique combination of transparency, rapid growth, and biological relevance. As research expands and the push toward New Approach Methodologies (NAMs) accelerates, the need for higher throughput, reproducibility, and precision is stronger than ever. This raises an important question: how can researchers keep pace with these demands while maintaining high-quality, reliable data?

In this article, we explore how automation is emerging as a key ally by helping laboratories streamline workflows, reduce variability, and unlock new possibilities in zebrafish embryo research.

Current Workflows in Zebrafish Embryo Research

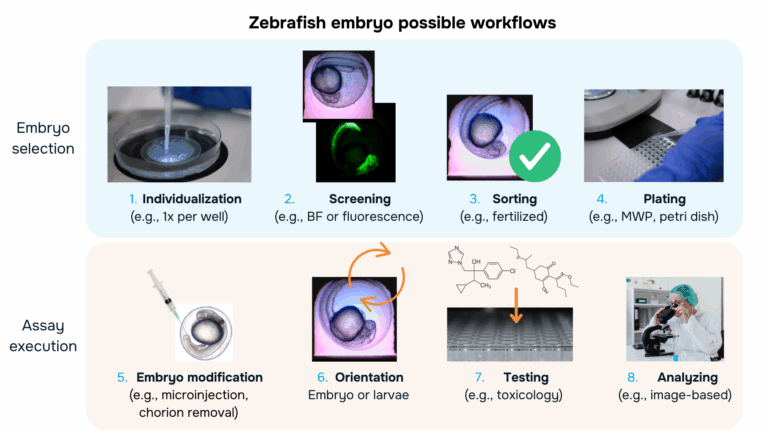

Typical zebrafish embryo workflows can be divided into two main phases: embryo selection and assay execution. Typical zebrafish embryo workflows can be divided into two main phases: embryo selection and assay execution. The visual below illustrates these workflows, highlighting common steps that may be included depending on the application, the protocol, and the needs of each researcher.

Embryo selection

Zebrafish egg workflows typically rely on a series of manual steps that start with egg collection and continue through selection, including individualizing, screening, sorting, and plating of each entity. Researchers visually inspect embryos under a microscope to remove unfertilized or nonviable eggs and to select specimens at the appropriate developmental stage for downstream applications. These early selection steps are essential to ensure uniformity, prevent contamination, and support the reliability of high-throughput assays for toxicity or drug efficacy. However, despite their importance, these procedures remain time-consuming, labor-intensive and operator dependent: the small size of embryos, the large number of samples required, and the need for careful manipulation create significant bottlenecks.

Individualizing

After embryo collection, individualization can be the first step to organize the sample for downstream work. In manual protocols, this involves transferring one embryo at a time into separate wells, usually in a Petri dish or multi-well plate, using a glass Pasteur pipette or fine plastic pipette. This careful placement prevents embryos from sticking together, reduces mechanical stress, and ensures that each specimen can develop under controlled and comparable conditions.

Screening

Once embryos are individualized, they are typically screened under a microscope, either in brightfield or fluorescence, to assess key quality parameters such as fertilization status, morphology, and developmental progression. Researchers manually examine each embryo to identify unfertilized, damaged, or abnormally developing specimens, as well as to confirm the desired developmental stage for the planned experiment. Fluorescence screening is often used when transgenic lines are involved. This manual inspection is essential for ensuring sample uniformity and experimental reliability, but it is also time-consuming and highly dependent on the operator’s experience

Sorting

Following screening, embryos are sorted to assemble the groups needed for the experiment. Based on the observations during screening, each embryo will be classified according to both the operator and the downstream experiment criteria. This step ensures that only the embryos relevant for the study will be carried forward and that each experimental group is consistent with the intended design, typically fertilized embryos. While essential for establishing clean and comparable sample sets, manual sorting remains an operator-dependent and time-consuming task, especially when working with large numbers of embryos.

Plating

Once embryos have been sorted, they are manually plated into individual wells of multi-well plates or Petri dishes, depending on the experimental setup. Using pipettes, researchers carefully transfer each embryo to prevent damage and ensure proper positioning, which is important for subsequent observation or treatment. Proper plating allows for sample’s traceability, controlled exposure to compounds, uniform imaging, and accurate data collection for each embryo. Despite its importance, this step is labor-intensive and limits throughput, as careful handling is required to maintain embryo viability and avoid errors. For example, manually positioning embryos into 96-well plates can require two skilled technicians working for three hours to prepare around 30 plates, an average of 12 minutes per plate, making the process physically demanding, error-prone, and difficult to scale (1).

Assay execution

Once the pre-selection of embryos has been realized, the experimental assays can be carried out. This may include further embryo modification or specific re-orientation of the embryo or larvae, before applying treatments such as chemical compounds or drug candidates, and performing image-based analyses to assess morphology, development or any feature of interest. Careful handling during these steps is critical to maintain embryo viability and ensure reliable, reproducible results across the experimental group.

Embryo modification

For specific applications, embryo might need additional modifications such as chorion removal or microinjection. Dechorionation involves mechanically or enzymatically removing its protection layer, i.e., the chorion, spherical protective chorion, from which they will hatch naturally at 2-3 dpf (3). This can be necessary for some toxicological assays or to obtain higher quality images. On the other hand, microinjection allows the insertion of different compounds (e.g., fluorophores, nanoparticles, bacteria, DNA constructs, etc.) which can be particularly useful for gene editing. It often involves the use of microinjectors handled by the operator under a microscope to treat each embryo. Although not very complex processes, caution is required to avoid damaging the embryo and processing large batches of embryo is very time consuming.

Orientation

Proper orientation of zebrafish embryos (e.g., on their side, ventrally, or dorsally) is often required to clearly visualize specific anatomical structures under the microscope. Correct positioning ensures accurate imaging and consistent data collection during morphological or functional assays. This step is often done by using diluted agarose for a better control (5). However these protocols often lack standardization, making their adoption limited.

Testing

After all of these preparation steps, the experiment can finally start. Test compounds, such as small molecules or environmental chemicals are carefully added to the medium surrounding the embryo at defined concentrations and time points, usually by using a pipette. Several official guidelines have been released in an effort towards standardization (6).

Analyzing

During the experiment, researchers manually monitor the embryos over time, scoring endpoints such as survival, hatching, morphological changes, organ development, or specific fluorescence under a microscope. Common examples include assessing cardiotoxicity by observing heart rate, neurotoxicity via spontaneous movement, or developmental effects by tracking body axis elongation.

The Role of Automation

Automation aim to address the time-consuming, variable and labor-intensive bottlenecks of manual zebrafish workflows by using robotic systems, imaging platforms, and computational tools to perform routine tasks with greater speed, consistency, reproducibility and standardization.

Regarding embryo selection, devices like our EggSorter cover all the steps from individualization to plating. By leveraging both researchers’ expertise and AI, it processes embryos in seconds with high accuracy, saving time, reducing errors, and ensuring standardized, reliable data for every experiment.

For embryo modification, automation efforts have been conducted both within academic laboratories and on a commercial scale. For example, automated dechorionation (enzyme-based) and placement of 1600 embryos could be achieved by combining a modified mechanical shaker to a customized robotic station (7). Concerning microinjection, laboratory setups using deep learning to guide automated microinjection resulted in precise delivery (8) while commercial devices started to emerge on the market (9).

Advances in embryo orientation have also been realized, with the development and commercialization of specific labware, which guide the sample into a precise orientation and can be potentially coupled to other automated devices (10). Other approaches such as microfluidic-based are explored within more academic settings (2).

Starting the experiment by adding the different compounds can often be performed by typical liquid handlers or other automated pipetting solutions.

Finally, imaging and behavioral analysis of zebrafish larvae can be performed using automated platforms such as ZebraBox from ViewPoint Technologies. It enables real-time monitoring and analysis of zebrafish larvae behavior, by tracking multiple larvae per plate, generating heatmaps, and delivering stimuli, while analyzing locomotion, learning, memory, sleep, and toxicity effects through a user-friendly interface. Moreover, recent advances in machine learning are expanding the capabilities and precision of zebrafish data analysis (11).

Conclusions & Outlooks

Automated platforms are transforming zebrafish research, enabling high-throughput, standardized, and reproducible studies in drug discovery, toxicology, and behavioral science. While many individual steps, from embryo selection to analysis, can already be automated, the major challenge is integrating these technologies into a single, seamless workflow. Future advances will likely combine AI, fluidics, and robotic handling to minimize manual intervention, linking sample preparation, manipulation, and high-content analysis. Such fully integrated platforms could not only accelerate research but also strengthen the regulatory acceptance of zebrafish assays, providing reliable, traceable, and reproducible data to support chemical safety and drug evaluation. The coming years are poised for creative re-engineering of existing technologies, making zebrafish an even more powerful model for scalable, predictive screening.

References

- Diouf, A., Sadak, F., Bereziat, L., Gerena, E., Fage, F., Mannioui, A., Zizioli, D., Fassi, I., Boudaoud, M., Legnani, G., & Haliyo, S. (2025). Combining deep learning and microfluidics for fast and noninvasive sorting of zebrafish embryo. Scientific Reports, 15, 37778. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-17946-7

- Otterstrom, J. J., Lubin, A., Payne, E. M., & Paran, Y. (2022). Technologies bringing young zebrafish from a niche field to the limelight. SLAS Technology, 27(2), 109–120. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.slast.2021.12.005

- Westerfield, M. (2000). Removing embryos from their chorions. In The Zebrafish Book: A guide for the laboratory use of zebrafish (Danio rerio) (4th ed.). ZFIN. https://zfin.org/zf_info/zfbook/chapt4/4.1.html

- Rosen, J. N., Sweeney, M. F., & Mably, J. D. (2009). Microinjection of zebrafish embryos to analyze gene function. Journal of Visualized Experiments, (25), 1115. https://doi.org/10.3791/1115

- Kleinhans, D. S., & Lecaudey, V. (2019). Standardized mounting method of (zebrafish) embryos using a 3D-printed stamp for high-content, semi-automated confocal imaging. BMC Biotechnology, 19(1), 68. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12896-019-0558-y

- Organisation for Economic Co‑operation and Development. (2025). Test No. 236: Fish Embryo Acute Toxicity (FET) Test. OECD Guidelines for the Testing of Chemicals, Section 2. OECD Publishing. https://www.oecd.org/en/publications/test-no-236-fish-embryo-acute-toxicity-fet-test_9789264203709-en.html

- Mandrell, D., Truong, L., Jephson, C., Sarker, M. R., Moore, A., Lang, C., Simonich, M. T., & Tanguay, R. L. (2012). Automated zebrafish chorion removal and single embryo placement: Optimizing throughput of zebrafish developmental toxicity screens. SLAS Technology, 17(1), 66–74. https://doi.org/10.1177/2211068211432197

- Cordero‑Maldonado, M. L., Perathoner, S., van der Kolk, K.-J., Boland, R., Heins‑Marroquin, U., Spaink, H. P., Meijer, A. H., Crawford, A. D., & de Sonneville, J. (2019). Deep learning image recognition enables efficient genome editing in zebrafish by automated injections. PLoS ONE, 14(1), e0202377. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0202377

- https://www.objectivebiotechnology.com/autoinjector

- Funakoshi Co., Ltd. Product page #80394. Retrieved December 2, 2025, from https://www.funakoshi.co.jp/exports_contents/80394

- Jones, R. A., Renshaw, M. J., Barry, D. J., & Smith, J. C. (2023). Automated staging of zebrafish embryos using machine learning. Wellcome Open Research, 7, 275. https://doi.org/10.12688/wellcomeopenres.18313.3